Abstract: In the aftermath of the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi, Rwanda undertook a comprehensive reconstruction of its national identity. This article explores how memory politics, state narratives, commemorative practices, and educational reform contributed to shaping a unified national consciousness rooted in reconciliation, resilience, and transformation.

Introduction

The power of memory in nation-building is undeniable, especially in post-conflict contexts. In Rwanda, historical memory has been instrumental in redefining collective identity and ensuring "Never Again" becomes a lived reality. The state's role in curating memory—through truth-telling, symbolic acts, and institutional narratives—has played a decisive role in reconstructing a nation torn by genocide (Clark, 2010).

Constructing the National Narrative

Following the genocide, the Rwandan government introduced a cohesive historical narrative centered on unity, resilience, and shared citizenship. This involved reframing history through a lens that acknowledged past divisions but emphasized a collective future. The National Unity and Reconciliation Commission (NURC) was pivotal in promoting this narrative (NURC, 2018).

Commemorative Practices and Memory Politics

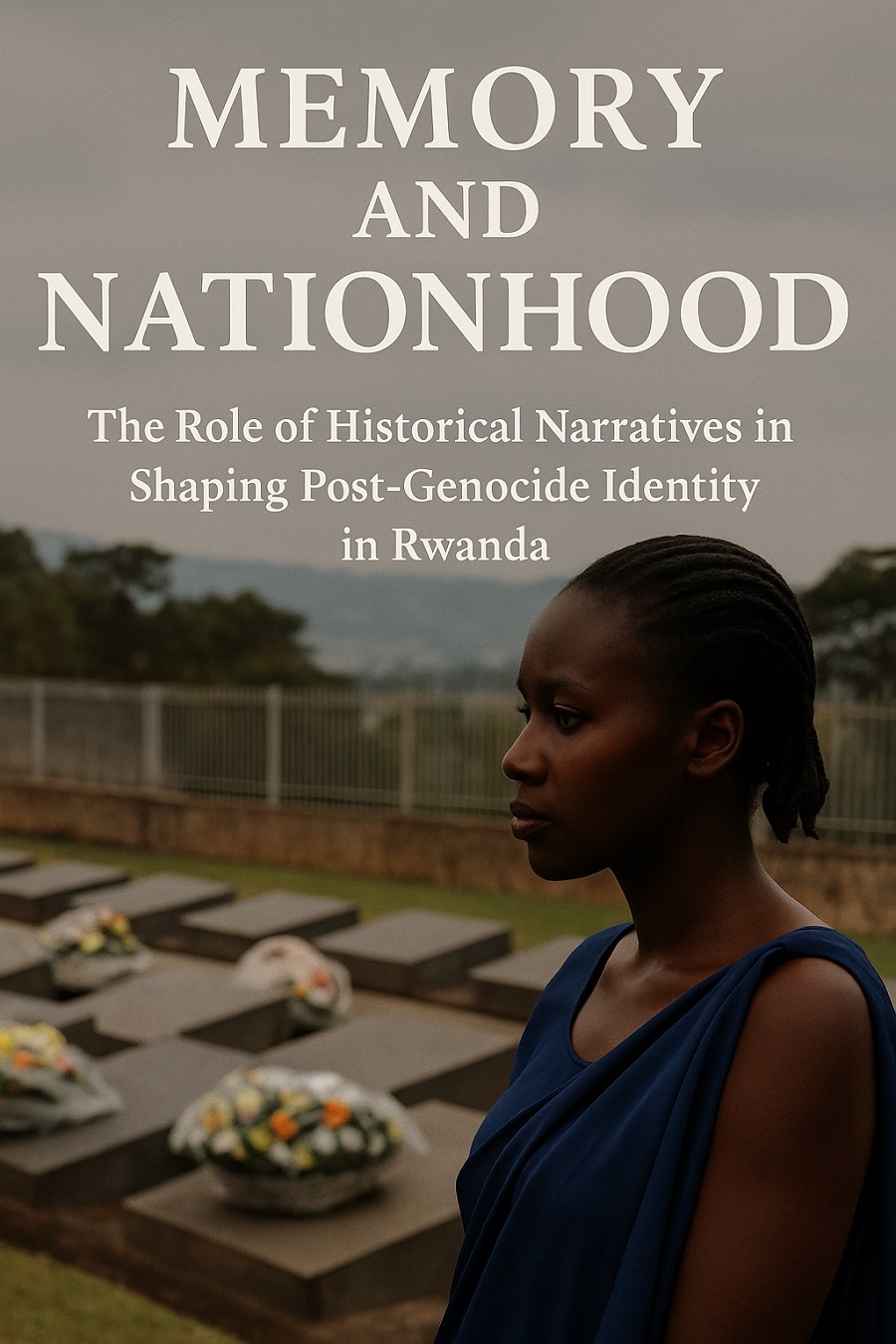

The annual Kwibuka (Remembrance) events have become a national ritual of mourning and reflection. Public memorials, such as the Kigali Genocide Memorial, serve as both sites of remembrance and pedagogical tools. These rituals embed the genocide in the national consciousness and are instrumental in cultivating a sense of moral obligation and shared history (Buckley-Zistel, 2006).

Educational Reform and Historical Memory

Rwanda's education system was overhauled to incorporate accurate genocide education. New curricula emphasize critical thinking, civic responsibility, and peacebuilding. According to the Ministry of Education (2022), these reforms aim to build youth identities grounded in tolerance and national pride.

Challenges in Memory Construction

Despite progress, tensions remain around the inclusivity of state narratives. Some scholars argue that alternative or marginalized memories are suppressed in favor of a singular, hegemonic memory. Balancing official memory with pluralistic narratives remains an ongoing challenge (Hintjens, 2008).

Conclusion

Rwanda’s case illustrates how historical memory can be harnessed to rebuild a fractured society. Through strategic storytelling, commemoration, and education, the country has fostered a new national identity rooted in remembrance and resilience. As memory evolves, so too does the vision of nationhood—one that aspires to unity without erasing the past.