Introduction: A New Kind of Chalk Dust

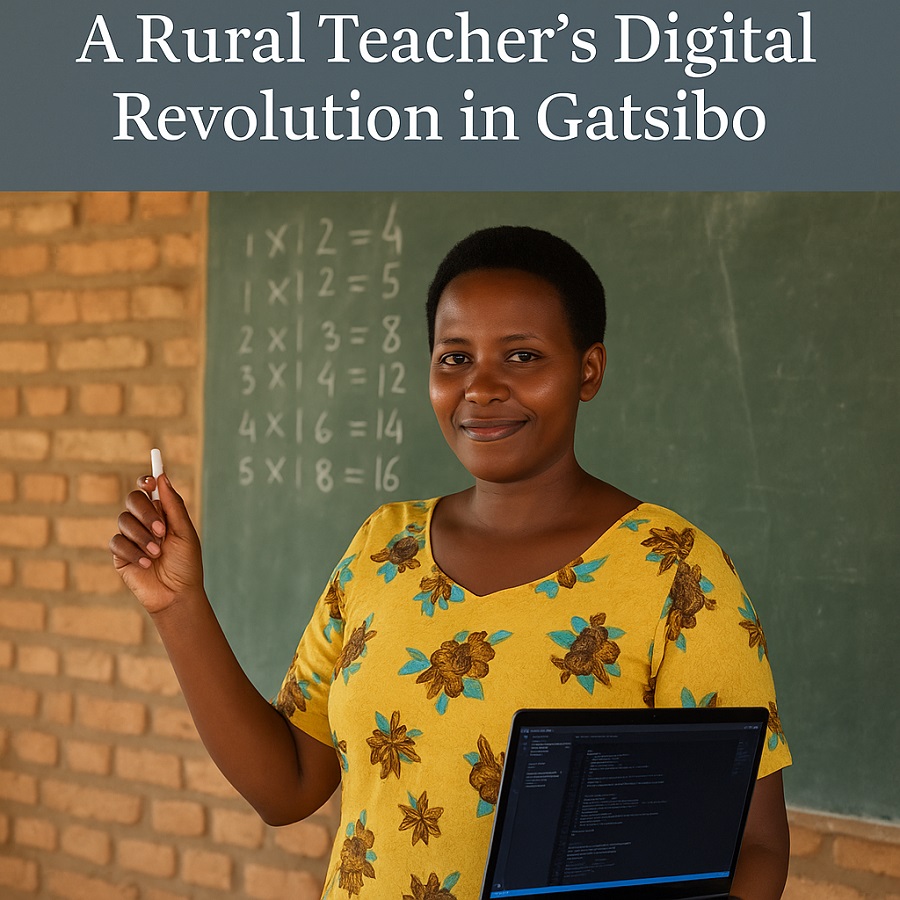

In a small classroom in Gatsibo District, Eastern Rwanda, the sound of keys clicking on a donated laptop competes with the usual rustle of exercise books. For Jeanne Uwera, a 34-year-old primary school teacher, this is not a contradiction — it’s a revolution. “I still use the blackboard,” she says with a smile, “but now, I also teach my students how to code.”

Jeanne is one of many educators rewriting Rwanda’s educational story — not from a national ministry or foreign capital, but from the dust floors of rural schools where Wi-Fi is patchy and power sometimes fails. Armed with a solar charger, a Raspberry Pi, and a conviction that rural children deserve digital futures, Jeanne is shaping the next chapter of Rwanda’s development.

Her classroom is modest—mud-brick walls, faded posters, desks made from old timber. But on one desk, a blinking cursor offers something radical: access. It’s here that children who have never seen a city skyline are learning HTML tags and flowcharts. For them, coding isn’t abstract—it’s a new literacy, a new language of possibility. Jeanne’s daily routine of hand-drawn lesson plans and solar-powered tech improvisation represents a quiet defiance of geography, scarcity, and historical neglect.

This fusion of chalk and code is not just a teaching strategy—it’s a political act. It asserts that innovation doesn’t belong to the privileged or the urban alone. By bringing digital tools into rural spaces, Jeanne is not only educating; she’s reshaping Rwanda’s future from the periphery inward, one keystroke at a time.

The Digital Divide in the Village

Rwanda has made great strides in ICT infrastructure, yet disparities between urban and rural schools remain stark. According to the Rwanda Education Board (REB, 2024), only 38% of public rural schools have reliable internet access. In many Gatsibo villages, students still walk kilometers just to find a mobile signal. A single smartphone in a household often serves as the family’s only window to the digital world—and even that is dependent on weather, battery life, and patchy reception.

But Jeanne believes the biggest barrier isn’t technology — it’s mindset. “Many people think village children cannot learn digital skills. That is wrong. They only need the chance.” Her words cut through a deeper truth: that infrastructure can be built faster than confidence. Skepticism lingers not only among policymakers but within the communities themselves, where digital learning is still seen as foreign, elite, or unrealistic. Jeanne sees her role as part educator, part translator of belief—bridging not only bandwidth gaps, but also generational doubt.

“Even some parents say, ‘Why teach coding when my child doesn’t have shoes?’” Jeanne explains. “But to me, this is not an either-or. It’s survival and strategy.” She sees digital literacy not as a luxury, but as a lifeline—one that might one day spare her students the hardship she endured. In that context, a blinking cursor becomes a symbol of defiance. It insists that rural does not mean backward, and poverty does not mean incapable. It is here, in the least connected corners of Rwanda, that the country’s vision of inclusive innovation will be most fiercely tested—and, if successful, most powerfully realized.

Teaching Python in Kinyarwanda

In her P6 classroom, Jeanne introduces students to basic programming logic using visual tools like Scratch, gradually building toward Python. “We start by writing commands like ‘turn left’ or ‘make sound.’ At first, they laugh. Then they learn.” The laughter, she notes, is part of the pedagogy. It signals wonder. Curiosity. The moment when a child who has never touched a computer realizes they can command it to move, respond, or think.

What makes Jeanne’s approach unique is her commitment to language inclusion. “I teach code using both English and Kinyarwanda. When children understand in their mother tongue, they build deeper logic.” This practice is more than translation—it is cultural scaffolding. Syntax becomes less foreign. Concepts like variables or loops are anchored in local metaphors: planting seasons, livestock herding, or traditional dance patterns. One child likened a ‘while loop’ to fetching water until the jug is full.

Jeanne is part of a growing movement that challenges the long-held assumption that technology must come wrapped in imported language. In doing so, she is not just building coders—she is shaping computational thinkers who are fluent in their culture as well as the cloud. “If we want true digital sovereignty,” she says, “we must start in our own language.” In her hands, Python isn’t just a programming language—it’s a tool of inclusion, imagination, and identity-building for the digital generation rising from Rwanda’s heartland.

Parents, Skepticism, and Cultural Shifts

When Jeanne first introduced coding, some parents were doubtful. “They asked, ‘How will computers help my child herd cows?’” Jeanne recalls. In a community where daily survival is measured in harvests and livestock, the idea of a child learning abstract code instead of practical chores seemed indulgent, even foolish.

But rather than dismiss concerns, Jeanne chose to meet them where they were—on porches, in kitchens, during walks back from the market. “I told them coding is like learning how to think, how to solve problems. It can help their children in any future — even in agriculture or business.” She spoke of weather prediction tools, crop-tracking apps, and financial planning software. Bit by bit, the idea shifted from alien to imaginable.

“At first, they thought I was wasting time,” Jeanne says. “Now, they stop me in the road to ask if their child can stay after class to practice more.” One of her students, 12-year-old Eric, recently won second place in a district digital innovation challenge for building a weather app using Scratch blocks. The project used local idioms and simple temperature indicators—a solution born from rural life, not imposed upon it. “Now,” she laughs, “they want laptops more than cows.”

But beneath the laughter is something serious: a cultural pivot. Parents are beginning to see their children not just as future farmers or traders, but as full citizens of a digital world. Jeanne’s work is not simply about access to devices—it’s about trust. Trust that a rural child can innovate. Trust that tradition and technology can walk side by side. And trust that education can stretch beyond the visible horizon, into futures once thought unreachable.

From Local Story to National Impact

Jeanne’s classroom became a case study in a 2023 policy paper by the Rwanda Education Sector Strategic Plan (ESSP), cited as an example of “localized innovation with national relevance” (MINEDUC, 2023). Her work also earned her a finalist spot in the African Union Teachers’ Prize for Innovation in Pedagogy. In a field where success is often measured by urban benchmarks and foreign accolades, Jeanne’s recognition signals something more profound: that systems-level change can rise from the soil, not just descend from policy towers.

What started as one teacher with a solar charger now inspires an entire district. Jeanne’s methods are being observed by school directors across Eastern Province, and her classroom has become an unofficial training ground for other educators looking to replicate her hybrid approach. “We still lack many things,” she admits. “But what we do have — creativity, resilience, love for our students — that is our software.”

That “software” is not a metaphor. It is the living infrastructure of Rwanda’s education renaissance: teachers who code lesson plans by lantern light, students who debug logic problems with no Wi-Fi, parents who now see opportunity where once there was only survival. Jeanne’s story has begun to ripple into curriculum dialogues, donor roundtables, and policymaker site visits. Her voice is not just a field report—it is a prompt for rethinking what educational transformation looks like when it’s driven from below, by those closest to the challenge and most committed to the change.

Conclusion: A New Vision, One Student at a Time

From chalkboard to code, from doubt to data, Jeanne Uwera’s journey represents more than technological adaptation — it embodies a philosophical shift. She teaches not just programming, but possibility. And in doing so, she affirms that Rwanda’s digital future will not be built only in boardrooms and data centers, but also in modest classrooms, one child and one command line at a time.

Her work is a quiet act of nation-building — not televised, not headline-grabbing, but no less transformative. It is the kind of slow revolution that happens under tin roofs and through whispered encouragement. Jeanne is not just coding a curriculum; she is scripting a new narrative for what it means to be rural, to be young, to be Rwandan in the 21st century. In a world too often fixated on macroeconomics and megabytes, her lesson is simple: real transformation begins where care meets courage.

As her students lean over their donated laptops, typing out their first lines of Python, they are doing more than learning to program machines. They are reprogramming what is possible. For a generation raised on both memory and ambition, Jeanne offers a new kind of roadmap — one that starts with a blinking cursor and leads toward a future that is both locally rooted and globally fluent.