The Civic Code: Building a Culture of Accountability Through Participatory Governance

By Prof. Vicente C. Sinining, PhD, PDCILM

VCS Research, Rwanda

Email: vsinining@vcsresearch.co.rw

ORCID: 0000-0002-2424-1234

1. Introduction

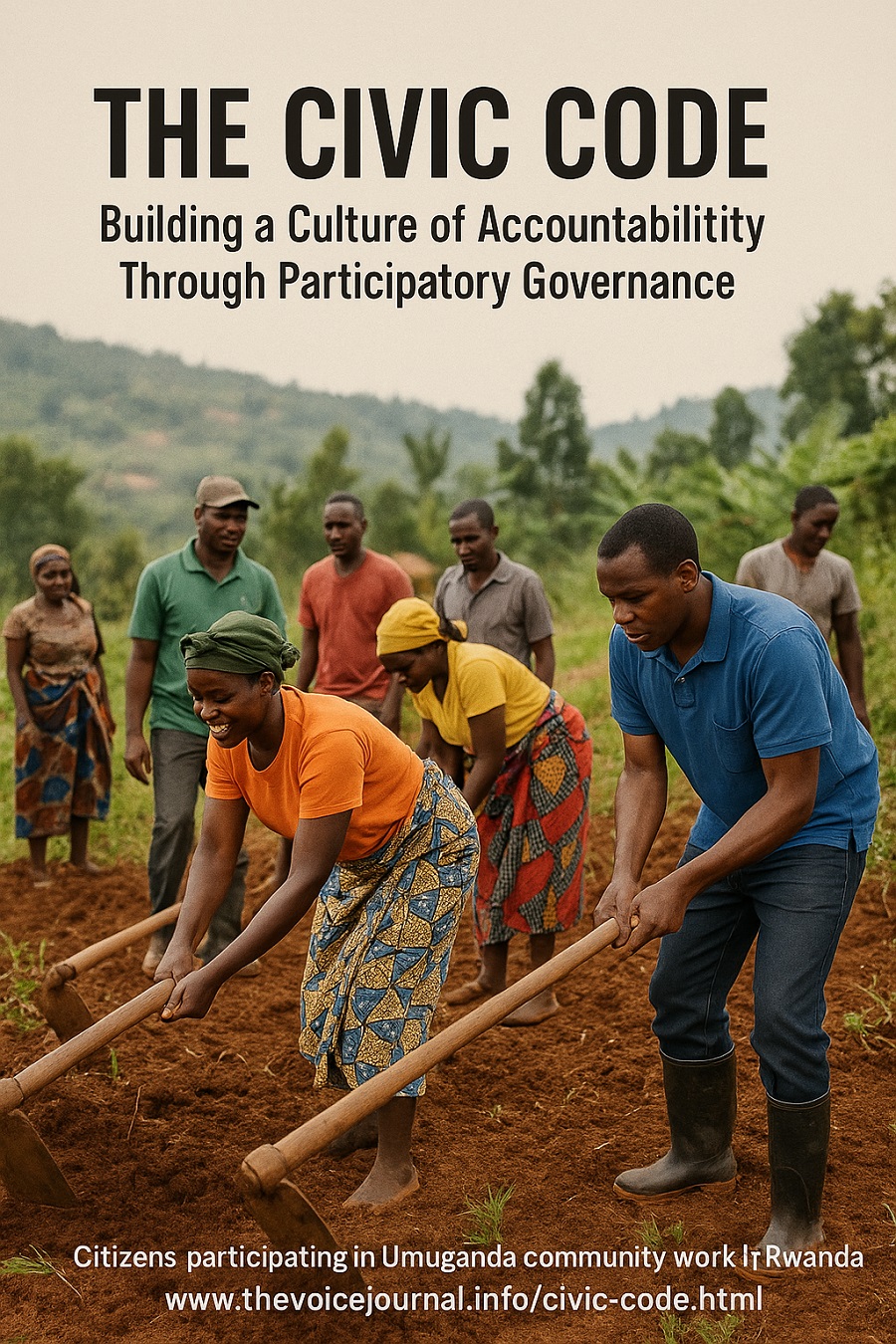

As Rwanda continues to reconstruct its social and political foundations in the wake of its traumatic past, one foundational force has emerged as both a catalyst and compass for national renewal: participatory governance. No longer confined to the realm of bureaucratic theory or elite policymaking, civic engagement in Rwanda has become an everyday practice—anchored in traditions of solidarity and reinforced through modern institutions. From monthly Umuganda community service to youth-led national forums and grassroots civic education, the country is cultivating a vibrant civic culture rooted in mutual responsibility, transparency, and shared accountability. This evolution is neither accidental nor symbolic—it is strategic, institutionalized, and deeply embedded in the architecture of the nation’s development agenda.

This article explores the contours of Rwanda’s evolving “Civic Code,” a living framework shaped not merely by legal statutes, but by social norms, ethical values, and participatory mechanisms that foster trust between citizens and the state. It is a code expressed in action—manifest in neighborhood cleanups, village assemblies, youth councils, and school-based civics curricula. By investing in civic innovation, Rwanda is redefining governance from a top-down directive to a bottom-up partnership, empowering its people not just as beneficiaries of policy but as active architects of the republic. In doing so, the nation offers a compelling model for countries striving to rebuild fractured social contracts and craft inclusive, citizen-centered governance from the ground up.

At its core, Rwanda’s civic renaissance represents a response to the deeper questions of post-conflict recovery and democratic legitimacy: How does a society rebuild not only its institutions but also its collective sense of purpose? How can governance be made resilient, not through coercion or dependency, but through civic empowerment? In Rwanda, the answers lie in a deliberate fusion of tradition and innovation—a governance model where ancient practices like Umuganda are reimagined as instruments of modern statecraft, and where youth engagement is not tokenized but institutionalized. Far from being a mere policy experiment, this participatory ethos signals a paradigmatic shift: a move from transactional democracy to transformative citizenship. As such, Rwanda’s experience provides both a mirror and a map—challenging assumptions about governance in the Global South and offering new pathways for building ethical, inclusive, and community-driven states.

2. Umuganda as a Governance Ritual

Umuganda, Rwanda’s monthly national community service day, stands as more than a civic ritual—it functions as a living instrument of governance. On the last Saturday of each month, citizens across the country convene to clear drainage systems, repair infrastructure, plant trees, or construct homes for vulnerable neighbors. Yet beyond its material outcomes, Umuganda cultivates a powerful civic rhythm. The visible participation of local leaders—mayors, cell coordinators, and sector officials—transforms these gatherings into dynamic spaces for grassroots dialogue, mutual accountability, and participatory decision-making. The process not only reinforces state presence but also humanizes governance by collapsing the distance between citizens and public officials.

This section examines Umuganda not merely as a nostalgic tradition or development initiative, but as a purposeful state-building strategy. It enables spatial and social equity by mobilizing citizens from both rural hillsides and urban neighborhoods under a common agenda of collective progress. Its participatory nature generates civic agency, fosters neighborly solidarity, and enhances responsiveness without the burden of coercive enforcement. Empirical studies have found that regular engagement in Umuganda correlates with higher levels of social trust and civic efficacy—key indicators of democratic resilience. For state actors, it serves as a low-cost, high-trust platform for gauging public sentiment, addressing local disputes, and reinforcing the social contract.

At a theoretical level, Umuganda challenges conventional distinctions between state-driven and citizen-led governance. It blurs the binary between formal and informal politics by integrating traditional communal labor with institutionalized public administration. Unlike many donor-driven models of civic engagement, Umuganda is endogenous—rooted in Rwandan cultural norms and sustained by collective will rather than financial incentives. In this way, it reframes governance not as a service to be delivered, but as a relationship to be cultivated. As other nations grapple with social fragmentation, weak state capacity, and civic disengagement, Rwanda’s experience with Umuganda offers an alternative script—one that repositions community work as both a democratic act and a foundation for participatory development.

3. Youth Councils and Intergenerational Governance

The National Youth Council of Rwanda stands out as one of the continent’s most institutionalized and impactful frameworks for youth civic engagement. Structured from the grassroots to the national level, young people are democratically elected to serve as representatives at the cell, sector, district, and national tiers. These elected youth leaders are not symbolic participants; they play a substantive role in shaping public discourse, contributing to policy deliberations, and monitoring government programs that directly affect their generation. Through these mechanisms, the council ensures that youth voices are not only heard but systemically embedded within the nation’s governance architecture.

More than a vehicle for political representation, the Youth Council has become a crucible for cultivating civic consciousness, leadership acumen, and public service values among Rwanda’s emerging generation. It facilitates intergenerational dialogue by creating institutional channels where young citizens engage constructively with government officials and community elders. In doing so, it addresses the perennial “credibility gap” often seen in governance—where the governed feel alienated from those who govern. In Rwanda, youth are not positioned as passive beneficiaries of state largesse, but as co-authors of national development. This participatory ethic strengthens democratic culture and prepares a pipeline of future leaders grounded in public accountability and civic responsibility.

In comparative terms, Rwanda’s Youth Council model redefines global expectations about youth engagement in the Global South. While youth inclusion in policymaking remains sporadic or symbolic in many contexts, Rwanda’s approach institutionalizes agency by equipping young people with voice, legitimacy, and structured roles in decision-making. It reflects a governance philosophy that sees youth not as a risk to be managed, but as an asset to be mobilized. By anchoring youth participation in democratic processes, Rwanda not only responds to the demographic realities of a youthful population but also lays the groundwork for sustainable, inclusive leadership. This model offers valuable insights for other nations seeking to close the generational divide and harness the civic potential of their youth as co-drivers of national transformation.

4. Civic Education and Institutional Trust

Since 2015, Rwanda has institutionalized civic education as a cornerstone of nation-building, embedding it across formal education systems, community trainings, and national mobilization programs. Known as Itorero ry’Igihugu, this initiative revives pre-colonial traditions of communal learning and moral instruction, repurposed for a modern republic. Through structured sessions in schools, youth camps, local assemblies, and leadership retreats, citizens engage with themes such as patriotism, public accountability, national unity, conflict resolution, service, and ethical leadership. Unlike generic civics courses found elsewhere, Rwanda’s model blends cultural heritage with contemporary governance principles to forge a civic identity aligned with national aspirations.

This section explores how Itorero has become a transformative force in shaping attitudes toward the state and citizenship. Far from being a top-down indoctrination tool, the curriculum emphasizes dialogue, reflection, and values-based education. Evaluations by the Rwanda Governance Board reveal a strong correlation between participation in civic education programs and heightened trust in public institutions, particularly at the local level. Citizens who undergo Itorero report greater willingness to engage in community decision-making, increased vigilance against corruption, and a stronger sense of national belonging. Thus, civic education is not just informative—it is performative, forging a citizenry that is both aware of its rights and conscious of its responsibilities.

At a deeper level, Rwanda’s civic education strategy challenges dominant models of political socialization that often rely on passive transmission of facts. Instead, it offers an active pedagogy rooted in historical continuity and moral instruction. In a region often marked by political polarization and institutional distrust, Itorero presents an alternative logic: that civic unity can be cultivated deliberately through education that is experiential, contextual, and values-driven. As other nations seek to restore citizen confidence in democratic institutions, Rwanda’s approach offers valuable lessons in rebuilding civic trust from the ground up—anchored not in abstract theory, but in lived, culturally resonant practice.

5. Participatory Platforms and Policy Feedback Loops

Rwanda’s governance architecture actively incorporates citizen feedback mechanisms as part of its effort to institutionalize participatory governance. Platforms such as Umuganda meetings, community scorecards, citizen report cards, and suggestion boxes placed in public offices function as structured conduits for civic voice. These mechanisms allow residents to raise service delivery concerns, propose local development priorities, and hold officials accountable for their performance. Crucially, these are not ad hoc initiatives—they are formally embedded into administrative processes at all levels of government, creating a continuous dialogue between citizens and the state.

This section examines how these participatory tools have evolved from symbolic gestures to operational pillars of governance. The design of these systems reflects intentionality: feedback is collected systematically, processed at the sector and district levels, and increasingly integrated into planning and budgeting cycles. Public institutions are required to respond to citizen concerns within defined timeframes, transforming governance into a responsive, iterative process. As studies from the Rwanda Governance Board suggest, awareness of these tools among citizens is growing, particularly in rural areas where local government is often the first point of state contact. These mechanisms not only enhance vertical accountability but also foster democratic habits such as deliberation, civic vigilance, and co-responsibility for public outcomes.

At a structural level, Rwanda’s feedback infrastructure represents a significant departure from top-down models of administration prevalent across many postcolonial states. By creating formal spaces for everyday participation, the government reconfigures authority—not as a distant, unresponsive force, but as a listening partner in development. This shift has profound implications: it legitimizes the state in the eyes of the citizenry, strengthens the social contract, and builds what scholars call “participatory capacity”—the ability of citizens to shape policy environments through sustained engagement. As digital governance expands, these analog platforms are being complemented by SMS-based surveys and online portals, further democratizing access to decision-making. Rwanda’s example offers a pragmatic model for other nations seeking to move beyond electoral participation toward more embedded, everyday forms of democratic practice.

6. Challenges and Critical Reflections

Despite its impressive innovations in participatory governance, Rwanda’s civic engagement landscape continues to grapple with substantive challenges. While platforms like Umuganda, youth councils, and community scorecards have broadened citizen involvement, concerns remain about the scope and depth of genuine participation. Political dissent is tightly managed, and observers have noted that some civic activities risk slipping into performative compliance—rituals of presence rather than platforms for voice. Additionally, structural barriers such as poverty, informal employment, and geographic remoteness can prevent marginalized groups—especially rural youth, informal workers, and persons with disabilities—from engaging meaningfully in civic life. These tensions raise important questions about who participates, how freely, and with what effect.

This section offers a critical reflection on the delicate balance between state-led mobilization and authentic citizen agency. It emphasizes the need to move beyond participation as mere presence, toward participation that influences outcomes. Safeguarding civic space requires not only expanding access to participatory platforms, but also ensuring institutional checks and balances that allow for critique, contestation, and dissent. Independent media, civil society organizations, and academic voices must be empowered to interrogate governance processes without fear of reprisal. Pluralism—both ideological and demographic—is essential if civic engagement is to be a force for inclusion rather than assimilation.

Looking ahead, the sustainability of Rwanda’s civic architecture may hinge on its ability to evolve from managed consensus to dynamic pluralism. This does not imply abandoning the gains made in social cohesion or national unity, but rather deepening them by embracing diversity of thought and experience. For participatory governance to thrive, it must accommodate difference, encourage deliberation, and protect spaces where alternative visions can be aired and debated. Expanding digital access, tailoring civic programs for informal sectors, and investing in civic education for adults—not just youth—could help democratize engagement further. Ultimately, the next chapter of Rwanda’s civic transformation will depend not only on the tools it builds, but on the freedoms it protects.

7. Recommendations for Deepening Civic Accountability

- Expand civic education curricula to include digital literacy, civic technology, and online participation tools

- Design inclusive civic engagement platforms tailored to the needs of informal workers, women, and rural populations

- Develop robust, data-driven monitoring and evaluation systems to track civic engagement outcomes at the district and sector levels

- Strengthen legal frameworks that safeguard freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly to protect civic space

- Foster strategic partnerships between youth councils, civil society organizations (CSOs), media, and local governments to co-create solutions

These recommendations aim to future-proof participatory governance by embedding civic resilience within Rwanda’s development model. By diversifying engagement methods and protecting fundamental rights, the state can cultivate a more inclusive, informed, and empowered citizenry—one that contributes not only to service delivery but to democratic vitality and social accountability.

More broadly, these reforms recognize that civic engagement must evolve alongside technological change, demographic shifts, and rising citizen expectations. By incorporating digital platforms, improving outreach to underrepresented groups, and institutionalizing feedback loops with measurable outcomes, Rwanda can deepen the legitimacy of its governance framework. Moreover, protecting civic space through enabling laws and independent oversight mechanisms will ensure that participation is not just invited, but respected. These measures will not only enhance the responsiveness of the state but also contribute to a more just, equitable, and participatory democratic culture—one capable of adapting to 21st-century governance challenges while remaining rooted in local realities.

8. Conclusion

Rwanda’s civic code is not etched in stone—it is lived, performed, and continually renegotiated. It unfolds in the rhythms of Umuganda, the debates of youth councils, the reflections of civic education, and the feedback channels embedded in public institutions. Rather than relying solely on formal constitutions or electoral cycles, Rwanda is cultivating a participatory ethos that extends beyond ballots and policy documents. It is a civic culture grounded in practice—where citizens are not just governed, but engaged; not just consulted, but co-responsible.

This paper has argued that Rwanda’s model of civic engagement operates on two levels: as a strategic tool for state-building and as a lived domain of citizen empowerment. Through deliberate design and cultural resonance, participation has been institutionalized in ways that both legitimize the state and empower the governed. In a global moment marked by democratic fatigue, rising authoritarianism, and widespread civic disengagement, Rwanda’s experience offers a provocative case of how civic trust can be rebuilt—if participation is inclusive, iterative, and woven into the daily fabric of public life.

Yet the durability of Rwanda’s civic architecture will depend on its capacity to adapt and remain open to pluralism, contestation, and critical reflection. Civic codes, like any form of social contract, must be continuously revised to reflect new realities, voices, and aspirations. As Rwanda moves forward, its challenge will be to preserve the gains of unity without suppressing diversity, to institutionalize participation without stifling spontaneity. In this balancing act lies the future of its democratic journey—a journey that, while uniquely Rwandan, resonates with global struggles to make governance not only representative, but responsive, inclusive, and deeply human.

9. References

- Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2008). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), 543–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032

- Government of Rwanda. (2022). National Itorero Commission Report. Kigali: Government of Rwanda. https://www.gov.rw

- Rwanda Governance Board. (2023). Citizen Report Card 2022. Kigali: RGB. https://rgb.rw

- Mutabaazi, E. (2020). Civic Education and Participatory Governance in Rwanda. African Journal of Governance and Development, 9(1), 45–62.

- UNDP. (2021). Local Governance in Rwanda: Building Social Cohesion Through Participation. United Nations Development Programme. https://www.undp.org

- Nzabonimpa, J. P. (2019). Decentralization and citizen participation in post-genocide Rwanda: A case study of community-based governance. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 54(1), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909618787593

- Fox, J. A. (2015). Social accountability: What does the evidence really say? World Development, 72, 346–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.03.011

- Gready, P. (2010). ‘You’re either with us or against us’: Civil society and policy making in post-genocide Rwanda. African Affairs, 109(437), 637–657. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adq037

- International IDEA. (2019). The Global State of Democracy: Addressing the Ills, Reviving the Promise. Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. https://www.idea.int

- Newman, J., Barnes, M., Sullivan, H., & Knops, A. (2004). Public participation and collaborative governance. Journal of Social Policy, 33(2), 203–223. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279403007499