“Sometimes, I walk with the gorillas in silence. That is when I know Rwanda is healing.”

– Jean Bosco, Park Ranger, Volcanoes National Park

Introduction: A Nation Rebuilt in the Mist

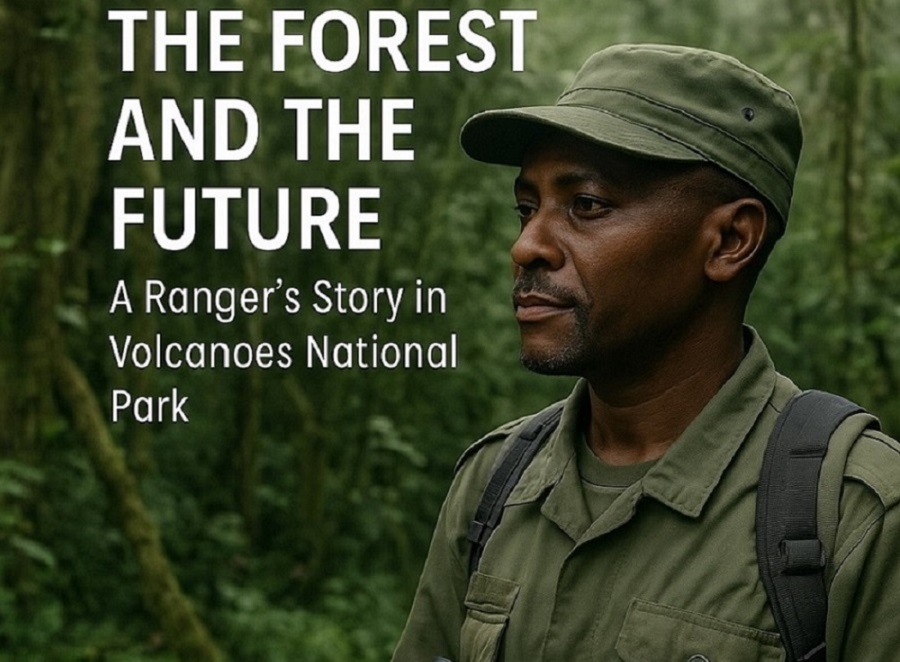

High on the slopes of Rwanda’s Volcanoes National Park, where mist clings to the eucalyptus and bamboo like memory itself, Jean Bosco readjusts his binoculars and scans the undergrowth. He is not just looking for gorillas. He is watching over them.

A senior ranger with more than 18 years of service, Jean is part of a new generation of conservationists whose work goes far beyond tracking primates. He is a bridge—between local communities and global travelers, between endangered species and national policy, between Rwanda’s violent past and its hopeful future.

This is the story of a forest—and the quiet diplomacy of those who protect it. It is a tale rooted not only in ecology, but in history, identity, and survival. For every footstep Jean takes beneath the canopy, there is an echo of Rwanda’s long journey toward healing—one in which conservation is not an afterthought, but a national ethic.

From Survival to Stewardship: The Journey of a Ranger

Jean Bosco was just 12 years old when his family returned to Rwanda after the 1994 genocide. “We came back from exile with nothing,” he recalls. “But even then, I loved the forest.”

He was recruited in 2005 into the park ranger program. “Back then, we were still healing as a country,” Jean says. “But protecting the gorillas—it gave us purpose.”

At a time when many young men drifted into urban unemployment, Jean took a different path—one forged in silence, patience, and deep listening. The forest became both sanctuary and school. Each patrol was a meditation in responsibility. “I learned to read the wind, to walk without sound, to know the difference between alarm and song,” he says. “And I learned to carry hope.”

Eco-Tourism as Development Diplomacy

Volcanoes National Park is home to over 30% of the world’s mountain gorillas. Jean Bosco leads tourists into the forest not just to show gorillas—but to represent Rwanda. “We tell them our story. They take it home.”

Gorilla tourism generates more than $25 million annually, with 10% shared with communities (RDB, 2023). Rangers like Jean are its most powerful ambassadors.

When tourists arrive—often from nations that once saw Rwanda through the lens of tragedy—Jean meets them not with pity, but with pride. “We show them life. We show them protection, and harmony,” he says. The trail becomes a diplomatic space where myths are undone and new narratives emerge—ones of green growth, local leadership, and quiet courage.

Between Conservation and Community: The Human Side

“There was a time,” Jean says, “when villagers near the park saw us as the enemy.” Today, with community programs and revenue-sharing, that narrative is changing. Jean himself led dialogue sessions with local leaders. “We are showing that gorillas and people can both thrive.”

These relationships are not built overnight. Jean’s work often involves attending community funerals, resolving land tensions, and mentoring young boys torn between poaching and poverty. “It’s not just about animals,” he says. “It’s about trust, and showing that conservation includes human dignity.” In this fragile but growing alliance, Jean walks a path shaped by empathy and diplomacy.

A Global Mission, Rooted in the Soil

Jean has represented Rwanda in Kenya and Germany. “They always ask how Rwanda did it. I tell them—it’s discipline. It’s unity. It’s the belief that nature can heal us.”

He often carries photographs of gorillas, but also of the families that live near the forest. His message to the world is nuanced: conservation must benefit both wildlife and people. “The global south has something to teach,” he says. “We protect not because we are rich, but because we know the cost of loss.” Rwanda’s model of eco-tourism is now studied globally—not just for its outcomes, but for the values behind them.

A Personal Reflection: What the Forest Taught Me

“I’ve seen gorillas mourn their dead,” Jean says softly. “Maybe they are not so different from us. This place holds memory. It holds possibility.”

There are moments, Jean admits, when the forest feels almost sacred. The low thump of a silverback’s chest. The hush before a storm. The quiet joy of seeing a baby gorilla take its first steps. “Those are the things I live for,” he says. “In those moments, you understand that protecting life—any life—is the highest work we can do.”

Conclusion: The Ranger as Diplomat, The Forest as Testimony

Jean Bosco is not a politician, but in every step he takes through the forest, he practices a powerful form of diplomacy: the diplomacy of protection, presence, and peace. His story reminds us that Rwanda’s transformation is written not just in policy, but in people—in voices from the field.

The forest remembers war, but it also shelters recovery. In Jean’s story, we see the living link between personal resilience and national renewal. As Rwanda moves forward, its guardians in green remain on the frontlines—not only watching over wildlife, but embodying a deeper truth: that healing, like stewardship, begins with care, courage, and commitment beneath the canopy.