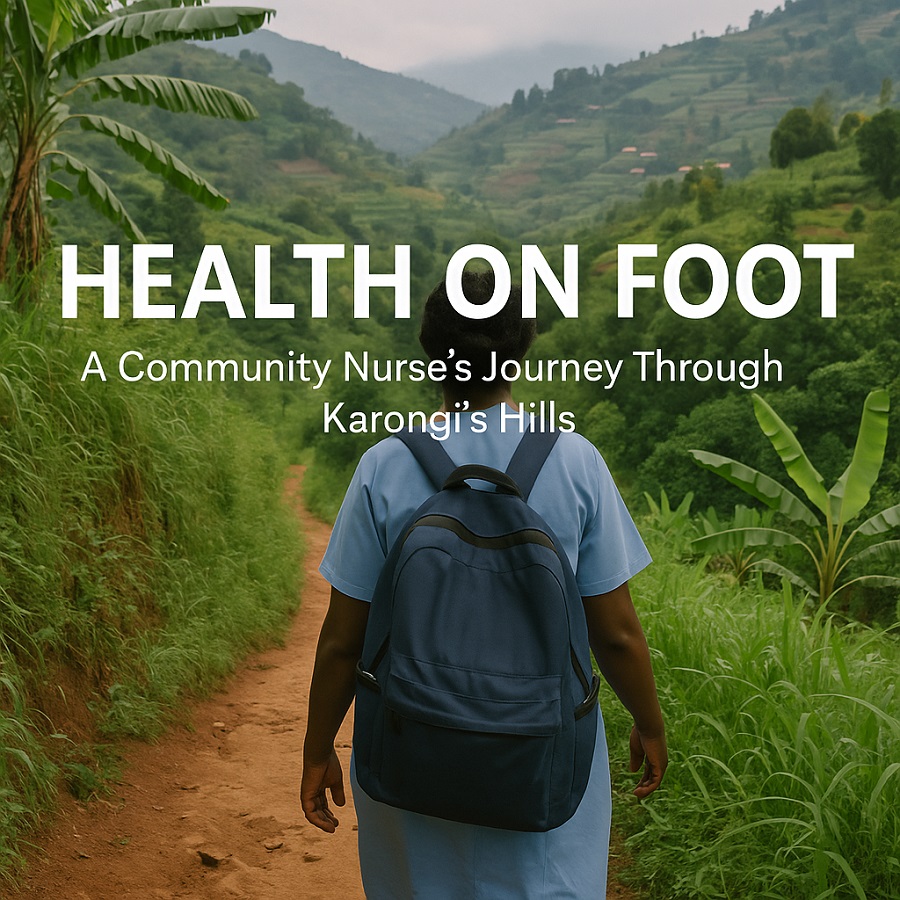

Introduction: Where Roads End, Care Begins

At dawn in the misty hills of Karongi District, Jeanne Mukandayisenga tightens the straps on her weathered backpack. Inside are the tools of a healer: a stethoscope, malaria test kits, vitamin supplements, and a mobile phone powered by a solar charger. Her clinic? A winding trail through banana groves and red clay roads. Her patients? Dozens of families spread across a dozen hills. Her vehicle? Her feet.

Jeanne is one of Rwanda’s 60,000 community health workers (CHWs), the quiet backbone of rural healthcare. She is unpaid, yet indispensable. She carries no title, yet she carries lives. She is the nurse who knocks on doors when mothers are too weak to walk. She is the reason a fevered child lives to see another sunrise.

Each morning begins with no guarantee—no schedule, no walls, no waiting room. Her patients range from newborns to elders, her office shaped by weather and terrain. She climbs hills not just with medical supplies, but with trust in her hands. In places where ambulances do not reach and clinics sit beyond the horizon, Jeanne is not only a caregiver—she is the health system itself, compressed into one determined silhouette walking toward a village before the fog lifts.

Her footsteps are quiet, but they speak volumes. They speak of a national model that dares to place health not in hospitals alone, but in homes, pathways, and conversations. In Jeanne’s story, healthcare becomes more than infrastructure—it becomes proximity, empathy, and moral resolve. This is where Rwanda’s resilience lives: not only in statistics, but in the calloused feet of women who walk until care arrives.

The Silent Infrastructure

In Rwanda, CHWs are the invisible infrastructure of the public health system. Supported by the Ministry of Health and local health centers, they deliver frontline care in areas where ambulances cannot reach and hospitals are hours away. Their work is part of Rwanda’s decentralized health strategy — a model praised by the World Health Organization for its efficiency, equity, and innovation. But to call it a “strategy” alone is to miss the human scaffolding that makes it work: thousands of women and men like Jeanne, moving silently through villages, turning policy into breath, into survival, into continuity.

Jeanne covers over 12 kilometers a day, often on foot, checking on pregnant women, malnourished children, tuberculosis patients, and the elderly. Her backpack holds both medical supplies and deep community memory. She knows who just gave birth, whose medication is running low, and which household lost a cow and might soon lose a child to hunger. She does it with no formal salary, driven by duty, compassion, and the memory of her own mother, who died from postpartum bleeding in a time when such workers did not exist.

That loss has never left her. It is stitched into every gauze roll she carries, every pulse she counts. “If someone like me had been there for her,” Jeanne once said quietly, “she might still be here.” In that sentence lies the unspoken power of Rwanda’s health infrastructure—not in steel beams or new clinics, but in the lived histories that now walk the hills in service of others. These are women who turned their grief into a grid of care that reaches the unreachable—not by technology alone, but by tenacity.

A Day in the Life: Diagnosing Without Walls

On a Tuesday morning, Jeanne visits a young mother named Clarisse, whose three-month-old baby has been crying all night. The air is thick with worry. Clarisse hasn’t slept. The baby’s skin is hot. Jeanne listens without rushing. With a small prick of the heel and a rapid diagnostic test drawn from her kit, she confirms what the mother feared: malaria. Jeanne administers the first dose of treatment under the shade of a banana tree, using clean water from her canteen. She then contacts the local health center to arrange a follow-up. “We treat what we can,” Jeanne says. “And we connect them to the system for what we cannot.”

By mid-morning, the sun is already harsh, but Jeanne continues. She walks another hour to visit Mugenzi, a 67-year-old man with high blood pressure. His mud-brick home has no electricity, but he welcomes her with a stool and a story. Jeanne takes his blood pressure with a portable cuff, records it on a Ministry-issued phone app, and gently reminds him to avoid salty broth. They laugh about his stubbornness. “When I see an old man walk without collapsing,” she says, “I feel my work is useful.”

What Jeanne does is not simply clinical. It is deeply relational. She is part nurse, part counselor, part epidemiologist with sandals and a memory that maps each household by heart. Her patients are not anonymous cases—they are names, histories, neighbors. Her rounds are not scheduled by algorithm but by intuition, trust, and urgency whispered from one household to another. There are no walls, no waiting rooms, no gowns. Only the landscape, the walking, the listening. This is community health as both science and sacrament.

Bridging the Health Equity Gap

Rwanda’s health system has achieved remarkable gains: maternal mortality has fallen by over 70% since 2000, and life expectancy has risen to 69 years. Clinics have multiplied. Digital platforms have scaled. But beneath the metrics lies a deeper engine of progress — one that does not speak in press releases or dashboards. These achievements are not just the result of technology or infrastructure — they are built on the backs (and soles) of CHWs like Jeanne, whose steps stitch the health system into the hills, one patient at a time.

Yet challenges remain, and they are not small. CHWs face chronic fatigue, limited supervision, and the emotional toll of watching preventable illnesses still claim lives in the margins. They operate in isolation, often without protective gear or consistent medicine stock. “Sometimes, I cry at night,” Jeanne admits. “But the next morning, I carry my bag and walk again.” Her resilience is not performative—it is a survival skill honed in silence, under rain, over terrain that tests the limits of both body and spirit.

In 2024, Rwanda’s Ministry of Health launched a new initiative to formalize CHW roles, provide stipends, and expand digital tools. For Jeanne, this is more than policy—it’s recognition. “I’m glad,” she says. “Not for me. I’ve done my part. But for the younger women coming after me, they deserve more than thanks.” Her words are not laced with bitterness, but with quiet conviction. She envisions a future where community health is not charity, but a career. Where care is not invisible, but institutionally honored. Where no woman has to choose between serving her community and feeding her children.

This is what equity means when it walks on foot: a system that reaches the unreachable, and finally turns around to embrace those who have carried it longest. Jeanne’s journey reminds us that progress is not just measured by how far a country can climb, but by how closely it walks with those who lift others along the way.

Conclusion: A Healing Journey

In the evening, as the sun casts golden rays over Lake Kivu, Jeanne returns to her home. Her feet ache, her phone battery is low, but her resolve is full. Tomorrow she will walk again — not because it is easy, but because it is essential. In her village, where roads taper into footpaths and clinics remain distant, care does not arrive on wheels. It arrives on foot. Where roads end, care must begin.

Her story is not just about rural health. It is about the quiet revolution carried out by Rwanda’s unsung heroes — those who do not wear white coats or speak from podiums, but who deliver health, dignity, and hope one footstep at a time. It is about labor rendered invisible by systems that depend on it, and about a vision of public health grounded not in machinery, but in memory, endurance, and radical proximity.

Jeanne is not just a caregiver. She is a witness to a new kind of infrastructure: one that speaks softly, walks daily, and heals collectively. Her journey affirms a national truth — that Rwanda’s most profound reforms are not always built with concrete or code, but with care that walks until it arrives. And tomorrow, she will rise again, not for praise or pay, but for people. This is what it means to serve where policy meets humanity. This is health on foot, and hope in hand.